It’s a Mad Mad World: US Pastures Threaten Human Health

The following article is one of the best I have seen about mad cow disease and food safety in America. It was written by my friend, Victoria Sutton and ran in the Paradise Valley Community College Puma Press. Looking at mad cow disease in this country from the inside, especially as a member of the media, is discouraging. I always see the same general and incorrect statistics and facts cited, along with glittering generalities.

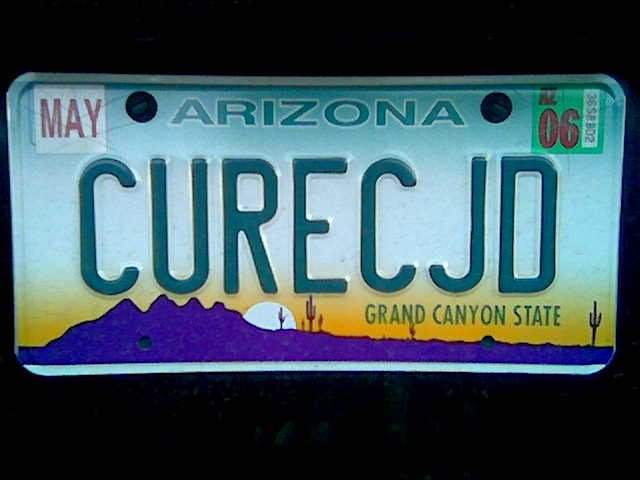

Victoria’s article doesn’t contain any of this! She doesn’t give the bogus “1 in 1 million” statistic about CJD. Every newspaper article says only one in one million people are infected by CJD, which is untrue. Once you start working the numbers and factoring in the age of the patient, it becomes one in 9,000. Then when you add more factors, it is one in 7,000 – but that is going to have to be another post for another day.

Here is Victoria’s bio:

Sutton, Victoria, AAS Environmental Health & Safety Technology, BS, Life Sciences, Ecology and Organismal Biology, Arizona State University; 8-year volunteer/rehabilitator for Arizona Game and Fish (permit under US Fish and Wildlife); has been researching and presenting general disease, radiation and management strategy information involved with Chronic Wasting Disease since 2002 and has been researching and presenting comparisons between Chronic Wasting Disease and Mad Cow disease for over a year. Also included in research and presentation interests is the management and radiation of avian disease. Presentations have been made to hunters, upper division life sciences classes at Arizona State Univeristy and at the Arizona Game and Fish Symposium.

Now for the article:

It’s a Mad Mad World: US Pastures Threaten Human Health

If you can sit down and assimilate all of the public information lately on diseases, think of how many are related to animals. Avian Influenza (Bird Flu) and West Nile virus are two major ones. However, there is another very serious animal-related threat in our midst, and it mysteriously seems to be avoiding the press like we should be avoiding it ourselves. It’s called TSE, which stands for Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathy, and it has several closely-related forms. One form of it is scrapie, which affects sheep. Another one is chronic wasting disease, which is spreading rapidly amongst deer, elk and even moose in the wild and on game farms. It’s also been found in mink and cats. If those still don’t ring a bell, think of a more familiar form: bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), or Mad Cow Disease, and think of it as a real danger that’s in the US; grazing state lands and dotting landscapes. Could it also be on our grocery store shelves?

On March 13, 2006, a cow in Alabama tested positive for Mad Cow Disease. This was the third publicly announced case in the US. The United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) public response is that the animal was older and ingested feed made from rendered beef, including the spine and brain tissue which is thought to harbor the infectious agent, a protein called a prion. A law was enacted in 1997, one year after the Mad Cow epidemic in England, to prohibit the brain and spine from entering cattle feed, but this Alabama animal was claimed to be older than the law and it is inferred it contracted the disease prior to 1997. The USDA stated that the animal didn’t enter the food system; rather it was buried on the farm. Routine would dictate that all the animals in the herd that shared pasture, corrals and feed with the infected cow will be tested. Now if Mad Cow is supposedly spread to cattle because they ingested infected tissues, it could be thought that the Alabama cow wasn’t the only older cow to eat the infected feed. They are social herd animals and as many as possible are contained in one area, sharing food, soil, barns and pasture. There could have been many, many more that also ate it, became infected and entered the food system.

According to the USDA, “FDA's 1997 animal feed ban rule has proven effective at keeping BSE out of the human food and animal feed supply.” The USDA also states that 652,697 cows have been tested for the disease since June 2004. The nation has about 95 million cattle. The number of cattle tested so far is less than 1%. It does not seem likely that such a low percentage of tested animals would warrant that the feed ban has ‘proven’ program effectiveness, and nothing in science is ever considered ‘proven.’ On March 14, 2006, the USDA announced plans to scale back testing, despite the fact a cow had tested positive in Alabama the day before. The new number of tested animals will be less than 1 tenth of 1 percent. It is estimated that 1 million cattle worldwide have been infected. It seems that the USDA position is that if it’s not found, it’s not a problem, and efforts are ensuring that it will not be found via decreased testing.

The TSE in cervids (deer, elk and moose), chronic wasting disease, is very similar to Mad Cow Disease and has prompted a frenzy of current research. There are some comparisons that can be made in terms of the treatment of the diseases. Cervids contract the disease without ingestion and positive cases are higher in larger groups. Cattle are intentionally kept in large groups. It has also recently been noted that the TSE in cervids has been found outside of the brain and spine and in other parts of the body, including glands, the stomach, liver, pancreas and muscle tissue. The USDA states that risky cattle body parts include the brain and spine, whereas the prion has been found in most tissues of cervids. The USDA allowed the infected Alabama animal to be buried on the farm, and the TSE in cervids is persistent in soil and may be contracted through that environmental route.

So exactly what can happen if a person is infected by a TSE? The disease is called Variant Creutzfeldt Jacob (pronounced ya-cob) Disease, or vCJD. CJD can also occur naturally and is called sporadic or genetic CJD. Like Mad Cow Disease and Chronic Wasting Disease, all CJD forms are degenerative disease of the brain, producing sponge-like holes in the tissues. Also like the TSEs in animals, it is fatal and without a cure. It causes memory loss, lack of coordination, shakiness, incontinence, muscle stiffness and the inability to speak. These symptoms are very similar to those found in a patient suffering from Alzheimer’s Disease, and it has posed great concern for many because it seems that now CJD may be misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s.

According to Dr. Colm A. Kelleher, author of Brain Trust: The Hidden Connection Between Mad Cow and Misdiagnosed Alzheimer's Disease, reports in medical journals state that approximately 5-13% of vCJD cases were misdiagnosed by physicians as Alzheimer's disease. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, it is estimated that 4.5 million people suffer from the disease. If 5-13% of these patients have vCJD, that number amounts to between 225,000 and 585,000 potential misdiagnoses. According to the science journal, Med-Research America (2005) 64, the number is in fact higher and is thought to be 5-30%.

The USDA states that the prevalence of Mad Cow Disease and the risk of contraction is very, very small, and that there is no evidence that people in the US will or have contracted it. Why would there be evidence? If a person is under the care of a physician for an ailment and dies from it, such as Alzheimer’s Disease, autopsies are not required and if a family wants one performed, it is very expensive. How would vCJD be discovered? According to Dr. Kelleher, the CDC does not require reported numbers on Alzheimer’s Disease, sporadic CJD, or variant CJD. The possibility of vCJD existing isn’t even tabulated by our disease authority.

There are many countries that have banned US beef, including Japan. According to a Japanese news source, Asahi (February 2006), “[Japan] government officials hinted at a further delay in resuming U.S. beef imports following a disturbing report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture that 20 sickly cattle were processed for human consumption. The animals in question had difficulty walking, which is considered an indicator of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). Although such cattle, known as "downers," were processed while Japan banned imports of U.S. beef, the U.S. government's report brings into sharp focus American laxity toward BSE, sources said.”

The bottom line is that science doesn’t know yet how TSEs are spread, but science knows that it does in more than one way, not only through ingestion. Science cannot yet state that cattle absolutely contract it without ingestion, but they can’t say it can’t happen, either. The unknown would seem to be a huge risk factor for the USDA and the Beef Industries, and if it’s not a risk for the government or for corporations that stand to lose everything if Mad Cow Disease is found more often, it should be considered a huge risk for us as consumers and as people who want to live long healthy lives.

If this is a concern for you, the only current solution is to drop beef from your diet. Watch the labels on other processed foods, and buy lamb and rice for your pets. The United Kingdom is reporting that dogs are contracting degenerative brain disorders, too. Until more is known, the unknown is a risk. To reduce the risk, buy your beef and dairy from a whole foods store and make sure it is free pasture and organic. These animals are typically healthier and less crowded than large-operation beef cattle.

The USDA was questioned on the comparisons and risk research currently conducted on Mad Cow Disease and Chronic Wasting Disease. The agency was also questioned as to why there is no information on their homepage, usda.gov, about the Alabama cow. The USDA did not comment. If the agency does comment, an update will appear in the May edition.

<< Home